It might seem strange to query whether an international body apparently in control of 40% of the world’s supply of oil can now be written off.

Yet following yesterday’s debacle in Vienna, it is difficult not to think just that. The era of OPEC’s primacy in oil may be ending.

By any reasonable standard, the meeting was a dismal failure. The priority for member countries arriving in Vienna was to promote stability of supply and make the case that factors beyond the body’s control are to blame for high prices, especially derivatives speculators, OPEC’s favourite bogeymen.

Ironically, if speculation is a problem, OPEC is making it worse. Spot oil prices fell ahead of yesterday’s meeting, before leaping by more than $2 a barrel as the fallout of the meeting filtered through the newswires. Other commodity prices also rose, anathema to Arab states concerned about regional unrest.

Whatever the cause of high and volatile oil prices – OPEC economists were floating the idea of a 15% risk premium yesterday – OPEC is not helping.

More generally, that the international producer’s cartel cannot at a time of serious regional upheaval, global macroeconomic concern and increasing price volatility is astonishing. Let’s look at the case for writing off OPEC.

OPEC’s production quota has failed to reflect production levels within OPEC countries for some time, with the former currently lagging the latter by 1.4 million pbd, almost the entire loss of supply resulting from the Libyan conflict.

Indeed, it was unclear yesterday whether the 1.5 million bpd production increase Riyadh pushed for meant 1.5 million bpd more oil would actually be produced, or only 100,000 bpd extra coming through the pipes, with the rest merely making up the gap.

As it was, OPEC could not even muster official acknowledgement that it’s quotas are out of touch with reality.

The sheer dysfunction of OPEC as a deliberative and strategic body is also a huge problem. Wednesday’s meeting shows that the cartel has splintered into two. The Gulf states of Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar and UAE pushed to boost OPEC output by 1.5 million barrels per day to 30.3 bpd in an effort to bring down oil prices. The other group – Algeria, Angola, Venezuela, Iran, Libya and Ecuador – voted against adding supply.

Yesterday was dominated by the acrimony between Saudi Arabia and Iran, which if unresolved (and it is unclear how it can be) scuppers OPEC’s ability to take substantive decisions.

The Kingdom, backed by other gulf producers including the UAE, is keen to promote regional stability and after the Arab Spring is seeking even closer relations with importing countries.

Saudi in particular is leery of signs of weakening global demand, is keen to promote regional stability and macroeconomic recovery. Having banked $214 billion from oil revenue in 2010, the Kingdom has sufficient cash reserves to soak up a price reduction of $20-30 a barrel and still fund massive domestic investment.

On the other side of the meeting room was Iran. Hostile to the West and economically disconnected due to sanctions, with a President under siege from within, the Iranian government needs high oil revenues now more than ever. Also, Ahmadinejad has drawn scorn within the region for his outspoken denunciation of Arab states wrestling with popular uprisings.

Similarly Venezuela, whose national debt is now priced for bankruptcy by international capital markets, needs a high oil price to mitigate the incontinent spending of its government. For Chavez, as for Ahmadinejad, $100+ oil may be a matter of political survival.

It is difficult to imagine these fundamental differences, which undermine OPEC’s role in stabilising oil supply, being resolved anytime soon.

There are also cultural problems that are coming to a head. OPEC has for some time been creating a version of the oil markets to suit itself.

There is no liquidity in oil markets, cry OPEC economists and delegates, only speculators, who need to be stamped out with uncompromising regulation, as if such a thing were even remotely probable, logistically or politically, in the western countries where hedge funds and investment banks are based.

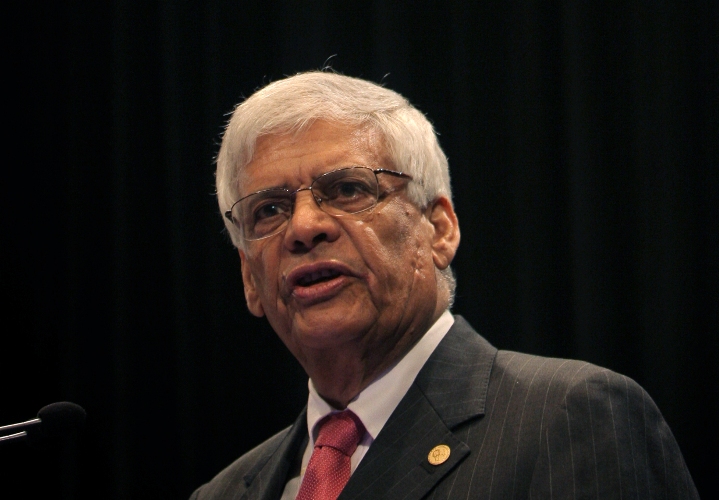

Tellingly, according to David Blair at the Financial Times, OPEC General Secretary Abdalla El Badri admitted to the press following the failed meeting that Libya was not mentioned.

Until recently, Libya was supplying global markets with around 1.75 million barrels a day of light, sweet crude. Today it supplies a few countries with 250,000 barrels.

How could a functioning producers’ cooperative, meeting to emphasise stability and credibility before an expectant global market, with the ostensible solution of raising production by 1.5 million barrels a day in the air, not even put on record that since their last meeting global supply has fallen but around the same amount?

Yet more worrying for OPEC than its dysfunction and sclerosis is its irrelevance.

At their zenith in 1973, OPEC producers accounted for 52% of total world oil supply. This has now fallen to 42%, with signs that this is likely to fall further.

According to BP’s annual Statistical Review for 2010, Oil production outside OPEC grew by 860,000 b/d last year, or 1.8%, the largest increase since 2002. Countries such as Russia seem able and willing to ramp up supply without being hamstrung by the considerations of membership in a producer’s cartel.

Additionally, some analysts believe Russia, not Saudi Arabia, has been the marginal supplier to advanced economies for a long time. The giant country has none of the problems afflicting the Arab world, and production rose to a near post-Soviet high of 10.26 million barrels a day in May. This is likely to export more than 10 million bpd for the foreseeable future.

In addition to Russia’s high and sustained production of over 10 million bpd, gas-rich countries such as Qatar are seeking to enter oil product markets through gas-to-liquid projects. The attractiveness of such projects is directly related to high oil prices.

Moreover, the world is shift from oil to gas for some of it’s needs. Long-term strategy reports from ExxonMobil and the International Energy Agency show a strong move to gas in meeting burgeoning electricity demand.

BP says gas consumption rose by 7.4% last year, the highest since 1984, with oil lagging at 3.1%. Oil remains the world’s leading fuel, at 33.6% of global energy consumption, but oil continued to lose market share for the 11th consecutive year, BP says.

Peter Voser, CEO of Shell, announced last week that the largest oil & gas company in Europe will be a majority gas supplier as early as next year.

Following yesterday’s meeting, a gulf delegate (perhaps the same one leaking statements before the meeting about the need for production rises) made it known that together with Kuwait and the UAE, the Kingdom plans to unilaterally raise production to meet increased demand, despite OPEC’s inability to act collectively.

“Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and UAE will each raise their output to meet demand regardless of OPEC’s status quo,” the Gulf delegate told the Dow Jones Newswire. This was later backed up by Ali Naimi, the Saudi Oil Minister.

So the largest member of OPEC is simply ignoring the cartel’s inactions that these days pass for decisions, despite the obvious rage this will cause and the risk it poses to the integrity of the cartel itself. It would be difficult to imagine a more stark rejection of OPEC’s quota system than that.

And in a world where oil demand is rising to meet oil supply, who needs a producers’ cartel anyway?

What do you think? Please comment below.